Events, talks, articles, announcements, and other news from the Nerd/Noir team

Evolving a Change Vision and Strategy for Platform Engineering

This case study provides an anonymized example of prior work for a Nerd/Noir client in the e-commerce sector. The scope of our engagement centered on a specific portfolio within the company, responsible for software services used by most of the other teams in the organization — a central dependency. Executive leadership decided to restructure their development process and practices to address the complexity of coordination between teams and emerging competitive forces in the market.

ESTABLISHING A CHANGE VISION: WHAT & WHY

A change vision establishes a baseline understanding of the opportunity, obstacles, and proposed countermeasures. It serves as a hypothesis for subsequent experiments that we will validate or invalidate as we learn through doing. It begins by diagnosing the most significant challenge the group faces in terms of impact:

Our product portfolio relies on a collection of services developed over many years. Building new features on top of them currently requires excessive coordination and effort. These services have become a bottleneck for the entire organization.

Common core system capabilities are at the heart of our ability to grow revenue and compete in the marketplace. Improving their usability is a business-critical effort essential to our long-term viability and competitiveness. Much of the system consists of legacy code using tools and languages that our development teams no longer have the skill sets to maintain or expand upon.

Then, the vision describes what the future looks like and what will need to change to get there:

Going forward, we will unify these services into a cohesive platform. The platform will enable reusable functionality stream-aligned teams can incorporate into their own services and applications to reduce dependency overhead within the organization.

This change is a joint effort between the product and engineering organizations. It will require a significant amount of collaboration, alignment, and compromise from leadership on both the product and engineering sides of the house, involving many tradeoffs and negotiations over an extended period of time.

STRATEGIES: HOW IN PRINCIPLE

Strategies provide a framework of principles for resolving conflicting priorities or approaches. These enabling constraints form a basis for decision-making across product and engineering organizations. They drive team and contributor enrollment in the desired change when supported by coaching from leaders and managers. We can ask, “Does what I’m doing align with our strategy?” When the answer is no, either the action is misaligned to a valid strategy or our strategies need additional tuning.

Modernize the platform to accelerate stream-aligned teams. We reduce the cognitive load of our stream-aligned teams. We will develop our system as a platform of discoverable APIs, front ends, and other components that stream-aligned teams can assemble to solve novel, domain-specific use cases. We will deprecate capabilities that no longer deliver value to the business.

Align the evolution of the platform with delivering new product opportunities. Our platform enables new product capabilities that unlock business value. Platform teams will develop these just in time for high-impact product initiatives. This represents a shift in how product and engineering prioritize and collaborate – decisions must balance product ambitions with platform investment.

Redistribute responsibility to local creators. Stream-aligned teams fully own the orchestrations and use cases specific to them. Platform teams provide reusable components to their customers, the stream-aligned teams. Communicating needs through system-level contracts such as APIs will replace expensive human-driven coordination.

Evolve collaboration patterns as the platform matures. Our journey begins with joint development – new platform teams working to create necessary system functionality with principal engineers and stream-aligned teams. We move towards a self-service platform that dramatically reduces coordination overhead and dependency management.

EXECUTION, LEARNING, EVOLUTION: HOW IN ACTION

A change vision specifies a desired set of goals but does not lay out the exact details of how to achieve them. Leaders and teams use the guiding principles to make coherent plans for implementing their strategies.

For this organization, changes can be grouped into three main stages:

Initial rollout includes the first changes undertaken by executive leadership, staff+ engineers, product managers, and team managers. These set up a framework for change management and contributor enrollment and include foundational changes that are difficult to reverse later on.

Early changes occurred at all levels of the organization, aligning team workflows to new processes and introducing new techniques and tools.

Ongoing steps reflect behaviors and processes that require longer times to adopt, feedback, and organizational learning, leading to improved processes and increased flow of value.

1. Initial Rollout

Conway’s Law observes that product and organizational topologies tends to mimic team communication structures. If the change vision differs significantly from the current state, the existing organizational structure might be an impediment. However, significant personnel moves and sudden shifts in roles, responsibilities, or reporting lines create a fog of uncertainty that can make change very difficult and put sustained progress at risk.

Team Organization: Leadership examined how much to restructure the teams based on the new core systems concept. There was an initial push to shuffle personnel amongst the teams based on various leadership coalition-related factors. However, the principle of team coherence was considered more important than specific domain expertise and ownership boundaries. This approach resulted in a smaller, more tactical first wave of employee moves, aimed at balancing skill sets and team sizes. As a result, the teams were stable enough to take on the more challenging demands of the transformation with minimal disruption and attrition due to change.

Understanding how products are envisioned, explored, created, and validated provides insight into bottlenecks, communication barriers, and learning or feedback loops. The organization’s current outcomes result from these processes, so changing outcomes necessitates altering the processes:

Product Development Life Cycle: Teams mapped their existing discovery and delivery workflow, finding buildups of work in progress led to long latencies, stale work, and delivery of non-value-added features. Using the map and historical data from previous product deliveries, they made initial changes to their discovery practices and delivery pipelines to more closely align the product and engineering teams.

Building organizational momentum requires clear communication of the strategy across the organization. Teams creating their action plans can generate enrollment, agency, and empowerment within the staff at every level—the governing constraints of the strategy act to keep those plans aligned.

Socializing the change: Leadership presented the plans for change as they were developed, keeping the organization informed with broad strokes at all-hands meetings and more details through smaller forums with presentations and discussions. Feedback was actively solicited from teams to promote team enrollment and discover obstacles to implementing the first process changes.

2. Early Changes

Aligning teams requires a shared perspective. Collaboration and negotiation are only viable when all parties have sufficient information to make informed trade-offs. Information radiators, standard metrics, and working agreements around value decisions foster the ability to shape the organization's actions to meet its current needs. Strategic constraints can empower teams to act locally in support of a global strategy.

Value Prioritization: Previously, product managers worked on their own initiatives with a single engineering team but often required skills or domain knowledge from other teams. There was no portfolio-level capability to prioritize the most valuable features, so the teams followed their PM’s lead, inevitably leading to scheduling conflicts.

The organization introduced a single common backlog spanning all teams. Product managers collaborated to establish a global priority for the shared feature-level backlog, as senior engineers provided design input for the platform architecture. In doing so, they could map risk and effort to inform priority decisions. The single point of truth for work enabled them to identify long-lead items, conduct early product discovery, detect issues in scheduling, and negotiate conflicting efforts. This led to a shorter cycle time for delivering features and less switching between multiple initiatives.

Reducing Delivery Size: Features had grown to the point where some had become “projects” that could last for months or quarters, so teams couldn’t safely or quickly pivot when new priorities arose.

Teams added constraints for story size and limited work in progress. They adopted techniques to refine work, splitting it into small and manageable chunks. Product management began evaluating promised versus delivered value in financial terms. Overall lead time for stories decreased significantly, as did the rollover of work between sprints. It became easier to change priorities, and the group attained literal agility.

Continuous Experimentation: Driven by continuous feature requests, the teams couldn’t make deliberate investments in their practices and cohesion. There was no investment at an organizational level in maintaining a high-level architecture. With smaller increments of delivery, it became possible to deliver more work. Senior engineers adopted experiments for platform evolution that targeted specific gaps in the current platform capabilities and ways for teams to add architectural rigor while developing existing features on the backlog. Most notably, they created new APIs to allow dependent teams to self-serve needs that had once been fulfilled through toilsome, manual requests. A platform takes shape.

3. Ongoing Steps

Implementing a strategy requires altering work processes, but only the broad strokes of process change can be visible at the outset. As organizational behavior shifts, secondary effects may manifest either due to old habits acting in a new process or because more immediate problems hide root causes. A crucial part of iterating on and refining strategies includes probing these new issues and adopting actions to address them. The organization uses empirical data to adjust its processes using established change management to perform double-loop learning:

Just-in-Time Focus: Initially, the common backlog helped us understand all the work in progress. However, existing commitments led product managers to start refining work with teams even though they had no capacity to begin working on the resulting stories. This issue was identified through cumulative flow metrics in the backlog. PMs continued to reduce the total number of features they focused on to reduce inventories of planned work. The development teams have retrospective items to improve delivery.

Process Evolution: The core management team held retrospective meetings at sprint boundaries to evaluate the effectiveness of the current process and create small countermeasure experiments to evolve their PDLC. The early meetings yielded many changes, leading to confusion about what experiments were in progress versus the established plan of record. Specific documentation of metrics to drive the adoption of changes, along with a WIP limit on changes, was used to make changes both impactful and more visible. The process stabilized considerably as teams became accustomed to new ways of working.

As the organization leans into new modes of work, their proficiency unlocks new opportunities. Things that were deemed unwieldy or impossible become tractable, and structured experimentation can test the boundaries of the feasible:

Team Coordination: As the organization worked on stories that required cross-domain expertise, the teams experimented with various methods to coordinate and share knowledge, thereby avoiding impediments caused by siloing. These have included whole-team pairings, “guest star” experts from other teams, and story splitting across well-defined boundaries. Coordination with teams in organizations outside the core platform remains challenging, as they need to be brought up to speed on the relevant processes and techniques.

The outcomes of the change vision typically manifest only as the overall emergent system behavior passes a threshold level of effort. “Slowly, then all at once.”

Legacy Architecture: Senior engineers continue to work towards retiring older, impossible-to-maintain codebases. Stories to stand up new services or place facades in front of older services have been added to the backlog and are actively refined by teams.

THE RESULTS

The actions aligned with the strategies described above yielded many measurable results.

500+ new products were created in 60 days via new APIs, replacing a laborious, ticket-driven process. In doing so, they also validated key architectural patterns used by their nascent platform.

A 48% increase in value delivered sprint over sprint. This was done by breaking months-long project deliveries into weeks-long value deployments, leading to greater agility in prioritizing work supporting innovation experiments.

>100% reduction in work rollover. Teams stopped starting and started finishing work in their two-week iterations. This capability lets major initiatives be dynamically reprioritized.

EVOLUTION: HOW STRATEGY MATURES WITH LEARNING

Realizing a change vision is hard work. Groups wishing to change must push past the desire to set a plan and execute that plan's steps. Making informed bets and implementing small yet rigorous experiments aligned with strategic principles that must be tested and refined requires constant involvement and a willingness to learn from failures.

Our approach to strategy is heavily inspired by the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act loop created by United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd. Specifically, we employ the strategy-focused adaptation of this loop adapted by Simon Wardley.

Some actions will achieve the goals of the change vision. Others might reveal new obstacles or challenges. Measuring results validates whether the strategically aligned actions are meaningfully advancing toward the vision or whether iterating the approach is warranted.

Continuous improvement, both gradual and step-wise, is a capability of a learning organization.

Scaling Smart: How Parallax Made The Shift From Project Thinking To Product Strategy

CONTEXT

Parallax, a growing SaaS company, struggled with predictable product delivery. Their product team, primarily from an agency background, naturally gravitated toward a project-based approach, focusing on scoping everything upfront, long planning cycles, and waterfall-style execution.

As a result:

The team regularly missed timelines, making it challenging to set customer expectations.

Work was not broken down effectively, leading to vague requirements and unclear priorities.

The product roadmap was often dictated by immediate customer needs rather than strategic vision.

Internal teams, including sales and customer success, lacked confidence in delivery commitments, leading to a disconnect between departments.

Without clear product ownership, decision-making was more reactive rather than intentional.

Parallax was at a crucial inflection point: to scale effectively, they needed to shift from an agency mindset to a product-driven approach: one that balanced strategic priorities with the realities of SaaS product development.

COLLABORATING WITH NERD/NOIR

Recognizing these challenges, Parallax partnered with Nerd/Noir to provide expert product strategy and delivery guidance. The focus was on equipping the team with the right mindset, practices, and tools to transition into a scalable, outcome-driven product organization.

Key initiatives included:

Shifting from waterfall to iterative development – Helping the team embrace agility, emphasizing working in smaller, more manageable increments rather than planning everything upfront.

Defining clear roles & responsibilities – Clarifying ownership within the product leadership team to ensure accountability and reduce confusion.

“Anne really helped us carve out roles & responsibilities amongst product leaders.”

Implementing structured planning cadences—Establishing predictable sprint cycles, refining backlog management, and introducing disciplined prioritization to align work with strategic goals.

Bringing engineers into the discovery process—Involving developers earlier in the planning cycle to ensure technical feasibility, reduce rework, and foster collaboration between product and engineering.

Improving internal communication and trust—providing visibility into what was being worked on, when it would be delivered, and why decisions were made, building confidence across departments.

“Anne was very good about meeting individuals where we are at—changing things while accommodating personal strengths & styles.”

Validating and reinforcing change: Coaching and support ensured the team felt empowered rather than overwhelmed, reinforcing that they were on the right track.

“She validated that what we were doing was way too much. A little external perspective went a long way.”

Over several months of part-time, targeted collaboration sessions, Parallax shifted from reactive product development to a more intentional, scalable, and customer-centric approach.

RESULTS

The transformation was immediate and impactful. With a more structured approach to product management and delivery, Parallax saw significant improvements:

Predictable, confident delivery—Teams moved from missing most deadlines to hitting 90% of their committed timelines, strengthening trust across the organization.

A scalable product strategy—Rather than reacting to one-off customer requests, the team could now balance immediate needs with long-term product vision.

“It feels like we’re finally operating like a real SaaS product team, rather than just reacting to every request that comes in.”

Improved cross-team alignment—Sales, customer success, and engineering gained confidence in product timelines, leading to stronger collaboration and better internal communication.

Faster time to value—By working in smaller increments, Parallax could release new features in weeks instead of months, accelerating customer feedback loops and driving continuous improvement.

A culture of ownership and collaboration—The team shifted from feeling like order-takers to true product stewards, making proactive decisions and taking pride in their work.

“We’re more collaborative with more ownership than ever. And if we ran into issues or hiccups, there was zero hesitation to reach out to Anne. She was always willing to listen and help us develop solutions.””

A key factor in this transformation was the strong coaching and support provided throughout the process.

By partnering with Nerd/Noir, Parallax successfully transitioned from a project-based group to one led by product strategy, setting itself up for long-term growth and scalability. This shift improved delivery predictability, empowered the team, strengthened internal alignment, and reinforced a product-first culture–key ingredients for sustained success.

Shifting Left to a T-shaped Team

A dojo challenge case study on how one team experimented to become more collaborative and cross-functional without losing speed using mob programming and value stream mapping.

What’s going on in this picture?

On the left, we have a developer. On the right? A tester. Witness a duo in flow.

They are working together in a mob programming session to write test automation code for a story that was “completed” downstream. The developer is getting a lesson on how test automation works within his team and the products they support from his co-creator (who happens to carry the label “SDET”). Opacity is decreasing!

What you can’t see or hear, what’s off-screen, is the rest of the team offering advice or listening attentively as their turn to drive or navigate the mob is about to come up. This is a central part of the mob programming technique where everyone crowds around a single laptop plugged into a large display and takes turns writing code and tests.

Mob programming creates an environment where skills transfer can happen. It’s something teams may do periodically or even full time. It is a weird idea. It’s counter-intuitive to the productivity-focused people (i.e. most of us). That’s OK. Just try it and you’ll probably come around to the idea that flow beats multitasking every time. I'll have more to say on this in a later post.

How did we get there?

As part of our dojo approach, we create a skills matrix for the team coming in to a 6-week challenge. We open the process by defining the term “T-shaped” and asking teams what becoming T-shaped mean to them in their context.

A T-shaped individual is often described as a “generalizing specialist.” They are someone capable of a lot of the typical duties any individual on a given team would need to perform. Full stack also works, if you want a more aspirational (or aggressive) synonym.

In the case of this team, calling themselves “Free Folk” in the dojo as the “Game of Thrones” series finale was upon us at the time, developers identified an interest in learning more about the end-to-end testing toolchain. Aside: the word “Free” comes from the team’s understanding that their dojo challenge is theirs to direct.

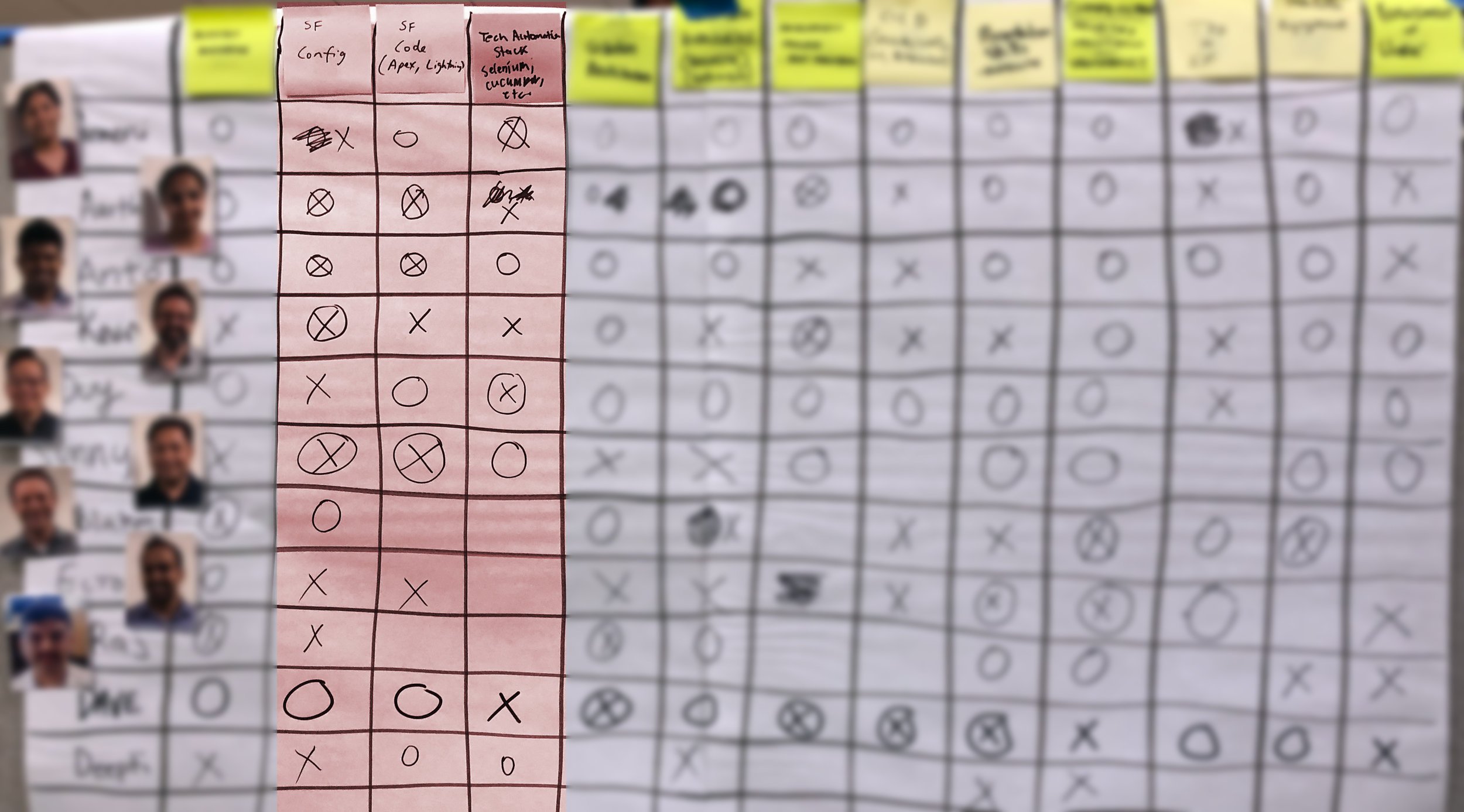

The red columns show you the developer stack (column one and two) and the SDET/tester stack (column three). This team has an opportunity to become more full stack. I see pairing opportunities!

In the dojo, we believe highly social and collaborative teams create T-shaped individuals. That is, the team needs to be self-sufficient and autonomous before the conditions for things like cross-training and co-coaching can really make a difference. Step one: eliminate external silos. Step two: remove internal silos.

SHIFTING LEFT BY DELETING INTERNAL QUEUES

Another term we see more and more these days is “shift left.” It originally comes from the testing world and boils down to something like “test earlier and more often in the development process.” This can be a shakeup to traditional, more waterfall testing approaches where QA sits as a kind of bottleneck to delivery at the end of a group’s pipeline waiting to inject defects as backflow in the system.

A cool thing about Free Folk: they were very transparent in sharing and explaining their current process. This is another key aspect of the dojo; you have experienced coaches to provide suggestions on subtle tweaks that could help the team accomplish their goals. In this case we suggested deleting internal handoffs and pairing through story delivery.

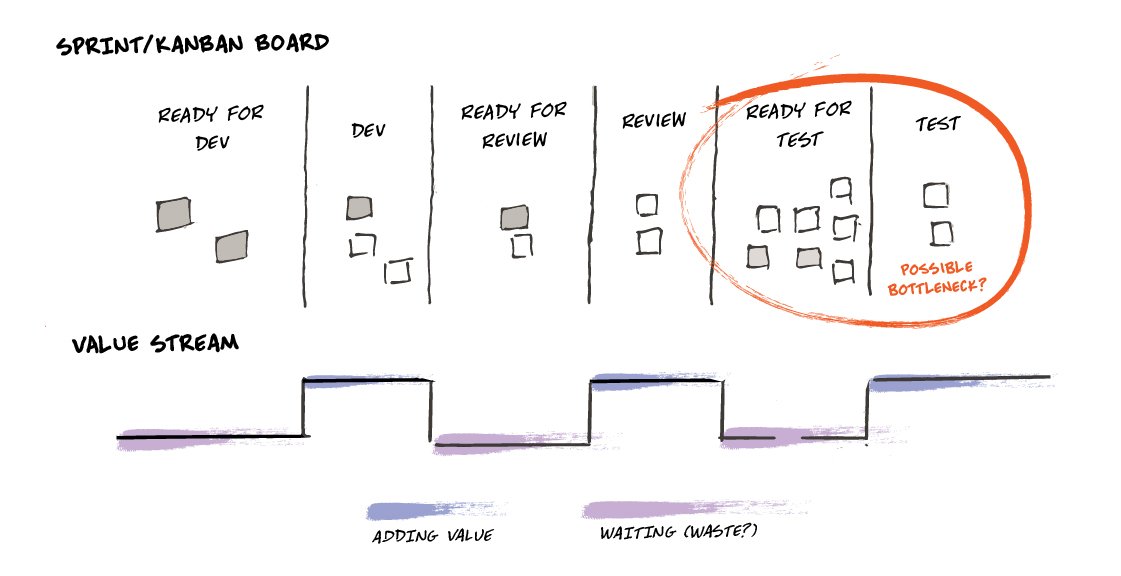

A cursory look at their sprint board in Jira revealed a number of wait states internal to the team:

We had a brief discussion about value streams and wait states and the waste of context switching (another post for another day) which lead to a consensus: let’s try collapsing these activities into one state within their pipeline. This means that they may end up pairing developer and SDET so every story can be worked as a vertical stack in a single pipeline that looks like this:

FOCUS AND COURAGE

Having a goal in mind is important.

"Free Folk” identified several goals to focus on in their dojo challenge, two of which lead us to the experiment of deleting wait states and trying mobbing and pairing:

Improving team dynamics and overall agility.

Become more T-shaped individuals.

David Hussman used a quote in his e-mail signature, "if you don't know where you are going, it's easy to iteratively not get there." Checking on what you're doing and experimenting with how you're doing it helps your team understand if a given practice yields an intended outcome. In this sense, the dojo model differs very much from classical teacher-student training with lectures and labs. We lead with identifying target outcomes and only then select the practices and tools we believe will help us get there.

We try not to do a lot of selling in the dojo. Challenge teams identify goals based on discussion and common understanding we help to bring to the fore. As coaches we are there to offer up suggestions for things we've had success with within the past — practices we feel comfortable teaching, coaching, and demonstrating. But it's the team's choice. The team sets its goals through a series of facilitated events that bring strengths and weaknesses into a shared light. Only then does the coaching begin.

The courage it takes to try new practices should not go unmentioned. I mentioned mob programming seems counter-intuitive at first. Propositions such as that can create friction against our internal instincts and conditioning toward personal productivity.

We propose some radical practices in the dojo, some seem bizarre at first (we ALL write this ONE piece of code) or even slightly scary (EVERYONE IS LOOKING AT ME TYPE). This is where courage comes into play. It takes time and reserved judgment to objectively decide if a practice that seems strange at first isn't for you or your situation. The courage comes in trying it before you reject it on principle alone. That's a good reason we choose longer periods of time for dojo challenges (4-8 weeks); it gives a team time to find the value in the practice for themselves, develop comfort, and adapt it to their workflow.

HERE TO HELP

Your dojo coach should always have your back. We are there to work with you side-by-side. We pre-negotiate delivery commitments and capacity down so we have the time for this kind of learning and experimentation. You will also see us suggest and fail in our own experiments and move on to the next one.

It's nice when everything lines up like this. My hunch is that these experiments, with this team, will open up new possibilities for their workflow, a workflow they're making their own. This team agency is one of the common and great meta-outcomes a dojo can help promote.

DevOps Dojos at Extreme Scale

A short story about my first introduction to the dojo model as a lead coach at Target’s DevOps dojo.

Learn how we scaled a massive DevOps immersive learning environment at Target in 2015.

DevOps dojos are an emerging trend in companies large and small looking to create full stack teams capable of releasing software continuously. I had the good fortune to join one of the largest, earliest, and most visible efforts in this space, Target’s DevOps Dojo . Did I mention large? 12 concurrent teams, a dozen product and technical coaches, 24 learning events per week, 150+ whiteboards, and infinite stickers. So, yeah, large.

An early definition of the dojo 6-week challenge. This, along with shorter workshop formats called “Flash Builds,” was a marquee offering of the original dojo.

WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY “DOJO?”

Dojos, as a concept, have been around for quite a while now. The word dojo is a Japanese term for any formal training place, most commonly one for martial arts. Classic coder dojos are a proven approach to creating a learning environment based on deliberate practice. Developers find a place to gather, select one or more practices (e.g. test driven development, refactoring, continuous integration), and run through one or more exercises to gain hands on experience.

Exercises are called “katas.” There are many ready-made katas: score a 10-pin bowling game , Conway’s Game of Life , make a program that can’t lose a game of Tic-Tac-Toe , communicate a solution architecture for a given domain , etc. Kata’s present relatively simple problems as a canvas for exploring and leveling up on a technical practice. I continue to use katas in workshops, interviews, and as a way of building and maintaining my programming skills.

Classic dojos and katas are useful, but the Target DevOps Dojo is a different animal. The objective of Target’s style of dojo is to get teams up to speed on continuous delivery in six weeks (12 iterations) and for those teams to carry forward the work after leaving. Target called this a “dojo challenge.” We were hired to help scale this approach, which I’ll cover in a minute. First, let's unpack the anatomy of a dojo challenge at the time of our landing.

A dojo challenge centers on a product team — product manager, coach, and engineers — working together toward a goal of continuous improvement. The challenge bit comes in when we compress iterations to twice weekly, which turns up the intensity of work. During this time the team is supported by one or more expert coaches who bring skill and experience with the tools and practices required to satisfy the challenge. Technical coaches are playing coaches. They are there to pair, ask meaningful questions, provide answers, pull in other specialists when things get esoteric, and ensure skills transfer. Their job is to become redundant.

I think of the Target Dojo’s challenges as more accelerators, but I try not to get too hung up on terminology. The point of DevOps isn’t to get good at Jenkins and Git. The point of DevOps is to create tight feedback loops connecting developer to user. Continuous deployment is valuable because it speeds up learning.

PIPELINE + PRODUCT = FASTER FEEDBACk

When I landed with Joel Tosi, my partner for the gig, we noticed that most teams in the Dojo were creating CI/CD pipelines. Not that creating a pipeline isn’t a valuable goal in itself, but we suggested framing a team’s time in the dojo around the delivery of a small product impact. That is, we introduced product thinking to their already-in-progress dojo model, a subtle but important twist.

When teams base their CI/CD pipeline development on a real effort, their pipeline gets much more realistic and useful. This tactic prevents over-engineering and waste due to speculation. There’s a great side-benefit: teams start learning how to balance continuous improvement while shipping value to their customers. In our experience, the former comes at the expense of the latter, especially in large enterprises.

Moving into practice we introduced DevJam’s collaborative framing technique. During framing, we gather a prospective dojo team and ask a series of questions:

What’s your team name and elevator pitch?

What delivery and learning goals do you have?

How do we know we’re meeting our goals in a six-week challenge?

Who cares about value/usefulness/feasibility?

What skills are required? Can we pull this off?

What are our standards for workflow, quality, and availability?

Are you fully committed to your 6-week challenge?

Once down this path, we saw the dojo open up to different kinds of product teams. For example, we ended up working with Target’s Learning & Development team to build training and other educational resources to support their company-wide agile transformation. It was a rewarding experience: focused by a frame, the close quarters collaboration and quick feedback loops of the dojo’s twice a week iterations yielded a much better product in a shorter amount of time.

150+ WHITEBOARDS & THE POWER OF PLACE

The Target Dojo itself occupies an entire floor in one of the buildings on their main campus. The space is dedicated, intentionally designed, and cavernous.

I remember the day the whiteboards arrived. All hands on deck! A half dozen of us wheeled the assembled whiteboards across campus, from one building to the next. From a bird’s eye view, we must have appeared as ants hot on the trail to the nearest picnic.

The whiteboards served a few purposes. They created walls between many concurrent teams. We’d use a whiteboard to place the frame from the beginning of the challenge in plain view. We’d use a whiteboard to self-organize a minimal process appropriate for the work that particular team was doing. We’d use a whiteboard to sketch and refine designs. All the while remodeling and wallpapering the team room for focus and purpose. In terms of team success, moving into a new space engenders focus and opens folks to coaching. They are making time in their busy schedules, coming into the dojo with commitment, intentionally. Teams are ready to do work.

There are a few powerful effects of having a dedicated space that should not be underestimated. The sheer scale of the space sends a clear message: we are all in on the dojo approach. Their leadership bought in, engaged, and supported the effort. From my vantage point, this support wasn’t just the key, it was the keystone.

BACKED BY A SOLID TEAM

My favorite thing about this dojo approach is the close collaboration with the internal coaches and support staff at Target. Close and energizing. Energizing and effective. Experiments went into practice at a startup-like speed.

This fast pace of experimentation is unusual for large corporations like Target. We were given a lot of latitude to ideate and test rapidly, everyone throwing their hypotheses and hard work into the mix. Like all good products, success comes down to the people involved: their skills, their involvement, their collaboration, and their follow-through and commitment.

No matter where you start your scaling journey, make sure you're doing it with the backing of a solid team.